The start of the current fall television season has highlighted the importance of social media in driving awareness and tune-in for new and established TV series as audience consumption habits continue to fragment across device and social platforms. With multiple apps being promoted by shows, networks and even TV service providers for checking-in to these broadcasts as well as fan pages and hashtags used to centralize the conversation around each episode, there is a growing need for audience measurement beyond the traditional Nielsen ratings.

The start of the current fall television season has highlighted the importance of social media in driving awareness and tune-in for new and established TV series as audience consumption habits continue to fragment across device and social platforms. With multiple apps being promoted by shows, networks and even TV service providers for checking-in to these broadcasts as well as fan pages and hashtags used to centralize the conversation around each episode, there is a growing need for audience measurement beyond the traditional Nielsen ratings.

The Nielsen Company is the de facto provider of the ratings system used to determine how the 60 billion in television advertising dollars are allocated amongst broadcast and cable network line-ups. The company relies on the behavior of 50,000 Americans across its sample of 25,000 households to extrapolate ratings for the nearly 115 million households with television sets in the U.S. The resulting ‘share’ of audience Nielsen attributes to each TV episode on a nightly basis ultimately effects which series get renewed or cancelled (for a great primer on how Nielsen’s TV ratings system works, check out this ESPN-style animated video on the topic from local Washington, DC creative agency JESS3).

Though with the number of households with television sets dropping for the first time in 20 years, on-demand video platforms taking viewing time away from traditional television and multi-tasking across multiple screens a growing reality, traditional means of measurement are failing to capture this evolving consumer behavior. While Nielsen is working on ways to aggregate this distributed viewing audience through its ‘extended screen’ initiative, the company isn’t measuring the actual activity on the social web occurring around the episodes being watched. This represents an opportunity for services that provide a platform for social engagement as well as companies that aggregate TV show-related conversations from across the internet to address this information gap. While both Facebook and Twitter have their own media-related initiatives that allow fans to interact with one another as well as with the shows and their stars, neither network focuses on quantifying this engagement on an industry-wide basis.

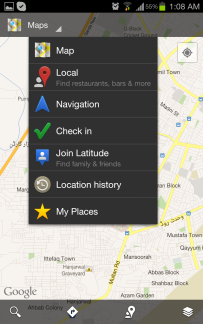

Services like BuddyTV, GetGlue, Miso and Tunerfish, on the other hand, have been built in a manner that can address this need. Having ridden the check-in wave popularized by location-based service Foursquare, these event-based social networks (EBSNs) capture when consumers are tuning in to watch television and aggregating the activity being generated around each show within their respective apps and websites. GetGlue, the largest of these services, already has more users checking-in to the most popular shows on its platform than the size of Nielsen’s entire sample audience, making it statistically valuable to the ratings conversation.

Even though the demographic make-up of EBSN users is not representative of the overall U.S. population (which Nielsen does try to mirror in selecting its households), check-in services make up for this by highlighting the actual activity of the most desirable audience to advertisers (18 to 49 year-olds) and not just projections. For advertisers this represents a unique opportunity to target these consumers in a highly engaged environment by extending their TV advertising for particular shows to the equivalent social web channels and mobile devices. To bring the desired scale to this type of opportunity though, these social environments need to be aggregated somehow.

That’s where companies like Bluefin Labs, General Sentiment, Social Guide and Trendrr come into play by not only aggregating publicly available social commentary but filtering and normalizing this data from disparate sources (EBSNs, Facebook, Twitter, etc.) to identify the underlying sentiment of a broader range of web users. This provides a more complete view of the engagement associated with shows across the social web in real-time as well as beyond the initial airing time slot of each episode. The resulting findings might be just the data set necessary to become the de facto social television rating to rival Nielsen.

Even with Nielsen’s recent ratings calculation glitch, it’s unlikely that the company will be replaced as the ratings system for the television advertisers industry in the near future. But as audiences for traditional TV continue to disperse across more mediums and content experiences, the need to compliment the ratings discussion, and ultimately how advertising dollars are allocated, with additional data will only continue to increase. This creates an opportunity for actual engagement-related metrics to gain equal footing with passive stream and tune-in projections over time.

So how do we get there?

While results from a recent NM Incite (a Nielsen/McKinsey company) study confirms the correlation between social activity and TV ratings, the opportunity for social television start-ups is in identifying and explaining the variations in popularity between Nielsen’s most highly rated shows and those series being discussed online and how to benefit from it.

The combination of tune-in and conversation activity make EBSNs the most compelling data set for social television ratings. The challenge is that the company that popularized the check-in, Foursquare, only recently passed 10 million users worldwide itself, a far cry from Facebook’s 150 million users in the U.S. alone. For EBSNs to reach Facebook-like adoption, they need distribution and a more automated process for socializing around TV shows (beyond the manual download of apps and checking-in to services). While BuddyTV and Miso have partnered with AT&T’s television service offering U-verse, GetGlue and Miso have integrations underway with satellite television provider DirecTV that enables subscribers to check-in to shows through DirecTV’s remote control. Other companies, such as Dijit, are by-passing traditional TV service providers entirely and competing for consumers with their own universal remote that layers in check-in functionality.

What social analytic companies lacks in proprietary data, they make-up for in business model by already working with advertisers and media companies to help them understand the volume and sentiment of chatter occurring online about their brands and shows across the social web. Gaining access to data on an exclusive basis from EBSNs and other social communities would be a key differentiator in winning the battle for advertising and media clients- the same companies that subscribe to Nielsen’s television ratings data. With so many companies vying for client dollars and mind share, the social analytics provider that can get the right media outlets partnerships to adopt and distribute their version of social television ratings can become the industry standard through sheer perception and market momentum.

Based on these factors, Trendrr, which launched a TV industry-specific real-time dashboard before the start of the fall television season could be that company. Considering Trendrr’s breadth of data sources (Facebook, GetGlue, Miso and Twitter) and how well they’ve embedded themselves into the online media landscape (partnering with the likes of AdAge, Lost Remote and Mashable to distribute their data and findings), the company is best positioned to become the social television ratings provider of the future.

What are the most likely outcomes?

Absent Trendrr or another one of these start-ups gaining the necessary client or user clout to grow into the de facto social TV ratings provider, the most likely outcome for the companies with the most traction in this market is an acquisition.

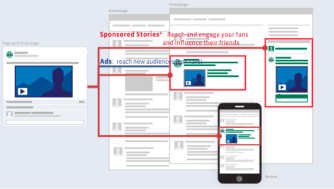

If either Facebook or Twitter decided to focus on provi ding analytics as a value-add to their advertiser and media clients, they would make ideal acquirers of these types of companies. For Facebook, adding a media-oriented check-in service to their massive user base would fit nicely with Facebook’s recent overturns towards the television industry and turn the acquired ESBN into the immediate and undisputed winner in the social television data game. Twitter on the other hand would benefit from acquiring one of the leading social analytics companies, as it would fill a large analytics hole in their offering. Even though the company recently stated its intentions to stay out of the enterprise market, the opportunity might prove to be too lucrative to stay out.

ding analytics as a value-add to their advertiser and media clients, they would make ideal acquirers of these types of companies. For Facebook, adding a media-oriented check-in service to their massive user base would fit nicely with Facebook’s recent overturns towards the television industry and turn the acquired ESBN into the immediate and undisputed winner in the social television data game. Twitter on the other hand would benefit from acquiring one of the leading social analytics companies, as it would fill a large analytics hole in their offering. Even though the company recently stated its intentions to stay out of the enterprise market, the opportunity might prove to be too lucrative to stay out.

Beyond Twitter, The Nielsen Company is a natural acquirer of a social analytics company since it compliments Nielsen’s existing ratings and research business. With the company having held an initial public offering at the beginning of this year, Nielsen also has the necessary capital to do this.

Beyond these entities, media companies and television platform could benefit from owning one of the EBSNs by leveraging these services to gain insight into user activity and drive additional tune-in for themselves or partners. Yahoo was the first to act on this, acquiring 12-week old IntoNow earlier this year and releasing an iPad app last week that integrates into Yahoo’s Connected TV framework. For GetGlue and Miso, who have raised capital from Time Warner and Google’s venture arm respectively, they already have likely acquirers in the fold. That being said, with the variety of relationships GetGlue (most recently with FX) and Miso (most recently with Showtime) have established with different broadcast and cable networks it’s not out of the question that one of these media partners tries to acquire either company to be their underlying social TV platform. The engagement data would be very valuable to any company negotiating with advertisers during the ‘upfront’ season as a way to justify advertising rates (beyond Nielsen’s rating data) for the next television season or provide brands with a new way to advertise to their intended audiences (for an additional cost or as a make-good).

Stay tuned. This market will only get more interesting.